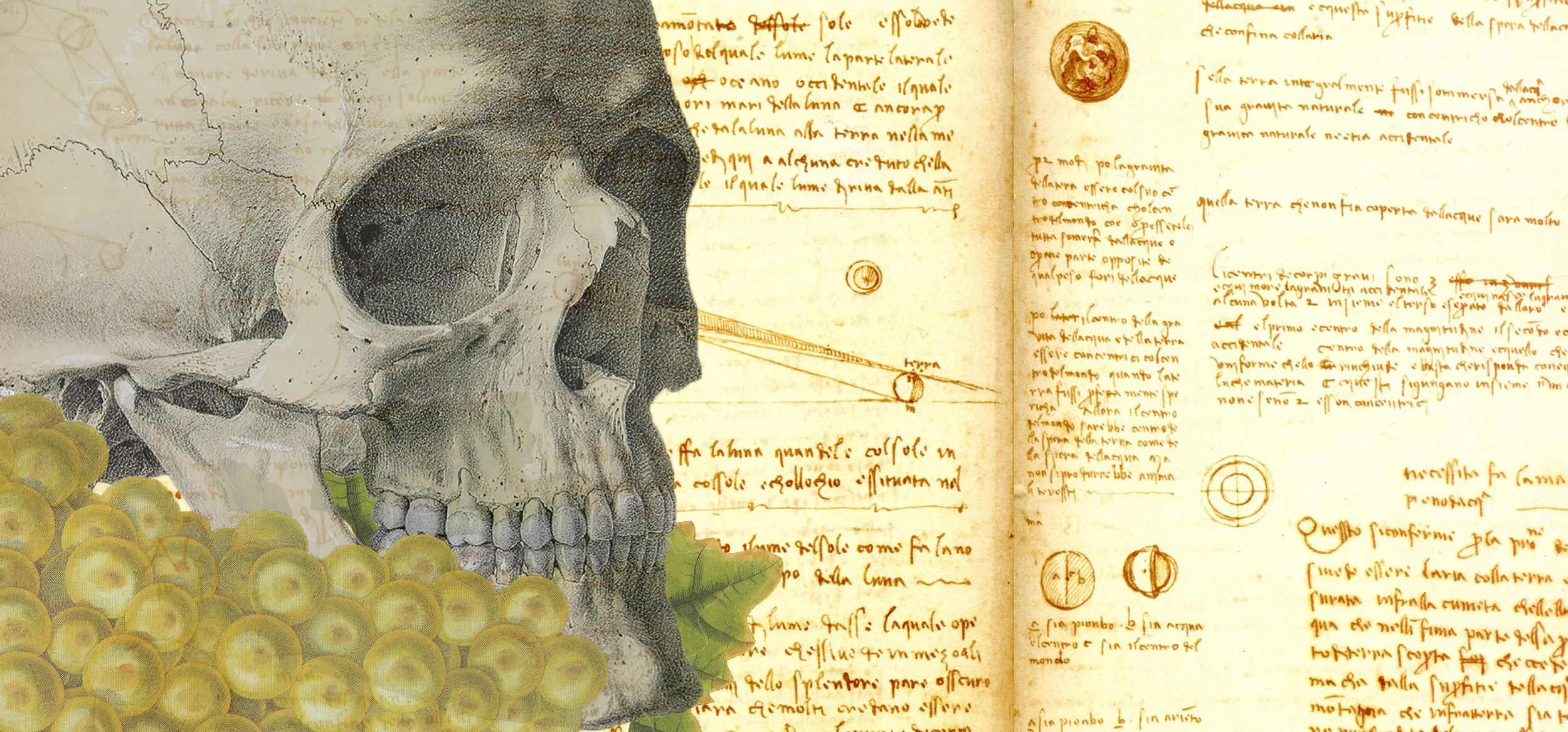

banner by Margaret Perry

A Humanist's Adventures in Anatomy

by Dr. Jeff Aziz

Sheep brains in coronal section look like slices of an exotic Basque cheese of a queasy and colorless color, the voids formed by the ventricles, like curiously symmetrical bubbles. For the first time, I am getting a three-dimensional sense of the ram’s-horns shape of the brain’s central plumbing system. I have just told my lab partners that I intend to sneak out early, when Dr. Jake Dechant, the anatomy professor who has allowed me to audit his Anatomy and Physiology class, says, “Want to see what this looks like in situ? In the cadaver?”

My plan to make a quiet exit is blown: there is just no way that I am going to miss this. We surround the perforated steel cart where the body of an elderly man lies face down, his skin already removed during the musculoskeletal unit, his muscles yellow and his tendons curiously golden from preservatives. Out comes the Stryker saw, that curious oscillating saw used by anatomists.

Removing the top of the skull, the calvaria, is not an easy process. Jake leans into the cadaver like an arm wrestler. The Stryker saw whines against the skull; the room fills with the smell of hot bone dust in a dentist’s office. The blade snaps off in the skull. Jake goes back in the toolbox for another Stryker saw, a vintage model with an all-stainless-steel housing and the chromed curves of a classic 1950s automobile. He is ripping it Old School.

Medical professionals, we are told, must learn to objectify the human body, to make of it a thing rather than a person, in order to function as people who will trespass on its private interior spaces, who must deal with bodies in life and in death.

With a slight rending crack, the top of the skull is removed. Is it just me, or is there a reverence to this moment? We all lean in. The brain is contained in membranes and connected to tissues beyond the skull through nerves that run through various foramina, the largest being foramen magnum, the grand aperture through which descends the spinal cord. Removed from the skull, the brain looks very much as you would expect from models and Halloween decorations. There is another aspect to this particular mass of tissue. This really was this man’s brain. His love of his mother, his knowledge of algebra, his opinion of the presidency of Lyndon Johnson all somehow resided in this cauliflower-like structure of gray material.

With the brain removed, the inside of the skull has a geography all its own, like that Jules Verne novel about the hollow interior of the Earth. We, students, are clustered around this terra inversa as Jake points out the sella turcica, the socket in the sphenoid bone in which the pituitary gland sits, like an egg in an egg cup.

I am a literary person, and I have to admit it: one of the things that have led me to this area of inquiry is the music of its particular language. The bones of the wrist are like a found poem. The Zonules of Zinn, sounding like the bad guys in a Buck Rogers flick, are actually the trampoline-like suspension of the lens of the eye. The mylohyoid groove is an anatomical feature of your jawbone or mandible, but somewhere out there is a prog-rock band looking for a name half this good. Then, there are the anatomical mnemonics. Would you believe that you can remember the branches of internal iliac artery by memorizing the curious sentence “I love going places in my very own underwear”? Well, it’s true.

My fascination with the field known as medical humanities began almost 30 years ago. My wife and I were in Florence, Italy, in March. We were looking for a museum she had discovered in one of those “curious traveler” type guides, la Specola, “the Observatory,” home to a notoriously quirky collection. It was here that I first encountered a conundrum.

The anatomical Venus or bambola venere is an artwork in wax. Imagine a woman languidly reclining on a chaise longue, her hair arranged in an elaborate braid over one shoulder. She barely meets your eyes as you enter. The superficial tissues of her chest have been removed, as well as her sternum, exposing the glistening surfaces of her lungs beneath a double strand of pearls. The muscles of the abdominal wall, the obliques, rectus and transverse abdominus, have been dissected away, and the intestines removed.

In the hollow, thus revealed, you can see where the aorta divides into the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and, nestled against the pubis, the strange Kinder Egg of the uterus, half peeled from its wrapper, the mesometrium. If this description troubles you, the presence of the anatomical Venus should do as well. She is a figure that appeals at once to scientific curiosity, voyeurism, and aesthetic rapture. She is disturbing in a distinctly gendered way.

The anatomical Venus raises a critical problem that engages me right now: the effort in anatomical representation to evoke the aesthetic, the beautiful. The 17th century Dutch anatomist Frederick Ruysch was known throughout Europe for the lifelike beauty of his anatomical preparations or prosections. The liquor balsamicum of dyes and preservatives with which he injected his preserved anatomical specimens was a jealously guarded secret. One of his preparations, the head of a young boy, so evoked the sense of life that Peter the Great of Russia, on a visit to Ruysch’s wunderkammer, is said to have lifted the head and kissed it with great affect. Peter’s part in the history of the anatomical Enlightenment is a strange one. In his own Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg, Russia’s first museum, Peter kept amongst other curiosities, the heads of one of his own and one of his wife Catherine’s former lovers, preserved in alcohol. Peter did not shrink from the violence he visited upon the bodies of others through his scientific diversions. His museum was notable for the living human specimens lodged or, if you prefer, imprisoned within. He kept, among other human curiosities, a number of dwarves, the French “giant” Bourgeois, and several hermaphrodites. These human spectacles were expected to display themselves to visitors, and all of them were subject to dissection after their deaths. The taxidermied skin of Bourgeois would be one of the Kunstkamera’s attractions for decades after his death.

The question of anatomical spectacle is a problem of modernity that, like the skin of Bourgeois, remains to trouble us. In his own time, Ruysch was famed for his artistic tableaux, his anatomies moralisées, featuring blood vessels and glands preserved to resemble an arrangement of corals or garden plants, along with the skeletons of infants, often posed to illustrate some moral lesson. None of these have survived to the present day, perhaps reflecting the fact that morals and attitudes toward such use of human materials are historical things, subject to changes of fashion and philosophy.

What is anatomical beauty? I don’t mean anything like the prettifying efforts of Ruysch’s daughter, the painter Rachel Ruysch, who clothed the preserved arms and heads of infants in fine lace sleeves and collars. What about the intrinsic beauty of the underlying structure of the body? What if you are one of those strange people who find beauty in the bony architecture of the orbit of the eye, or the vascular tree formed by the aorta, vena cavae, and pulmonary blood vessels as they emerge from the heart? Or in the functional elegance of the Circle of Willis, the arterial Beltway that guarantees the brain’s supply of oxygenated blood? On the one hand, we can see how these experiences of the beautiful emerge from an intuitive sense of organic functional wholeness and symmetry that is part of the way in which we perceive other bodies. On the other hand, and in the same instant, they confound our expectations of that wholeness. Bodily margins are breached; symmetries are disarticulated. Humanity is reduced to meat and bone.

In the “Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful,” the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke wrote, “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger… whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime.” “A source,” but only a source. The horror of death, experienced without the ability to distance ourselves, evokes in us only horror. For Burke, what creates for us the experience of the sublime are those “certain modifications” that allow us to put that terror in its place. The sublime, for Burke, is medicine practiced on another level, a momentary victory over the forces of entropy and decay.

If this strikes you as abstract and intellectual, it isn’t. You aspire to be a medical professional. You will confront this. The ideal body ultimately yields to the real body, distorted by disease, forlorn and motionless in death. You will probably find some way to deal with it. The ways in which we accommodate ourselves to the medical body are determined as much by history as by personal choice. The times are not long past when medical students in “gross lab” would place cigarettes in the mouths of cadavers assigned to them, posing with them in portraits that now strike us as tasteless and insensitive.

It’s early in my experience in the Anatomy and Physiology. My friend and colleague Jake Dechant whispers conspiratorially to me at my lab bench as he makes his rounds:

“After class, don’t leave: I have some cool stuff to show you.”

I never seem to get out of Anatomy and Physiology on time.

I walk into his office after most of the other students have left.

Into my hands, he puts a human skull, maybe four inches in diameter, light as a balloon made of bone and membrane. The dry amber surfaces of connective tissue that make up the anterior and posterior fontanelles are enormous translucent skylights into the cranial vault, clearly abnormal.

The skull of a hydrocephalic infant.

Hydrocephalus is caused by problems with the drainage system of the skull. Cerebrospinal fluid backs up in the ventricles, those hollows within the brain tissue. The developing brain shapes the skull, and the skulls of hydrocephalic infants are hugely distended, like the heads of aliens in ‘50s-era science-fiction films.

I feel, at this moment, much the way a person of faith must feel handling the bones of a saint. This is something wonderfully rare. It belonged to an infant whose name I will never know, who died almost before she had lived, possibly even before Jake and I were born. Her mortal remains were carefully preserved, for decades, because she has something to teach us. “Objectification” is a general term, even a necessary term, but it somehow fails to encompass the range and complexity, the real critical problem of our engagement with bodies, living and dead. I carefully set down this skull, as delicate as anything. As delicate as dreams.