Banner by Alisa Zhang

Learning How To Learn

By Cynthia Kumaran

Stacks of dusty textbooks border Sally’s desk. Her laptop screen’s white glare has pierced the pitch-black dorm room for what seems to be an eternity so far. She has been studying the same chapter in her chemistry textbook for the past three hours, and still feels like she does not know the material. Sally still has plenty to cover before her midterm exam tomorrow morning. Her mind is overflowing with anxious thoughts. What am I doing wrong? Between school, her job, and extracurricular activities, Sally cannot seem to understand how any student could get good grades in every class! With contempt, she glances over at her roommate, Abby — who gets amazing marks with the same packed schedule — peacefully asleep. What does she do that I don’t?

Like Sally, many students feel that with the amount of material they have to learn, their academic success is just impossibly out of reach. Knowing about the brain’s mechanism for learning is the first step in improving your own study experiences.

Starting with the basics, the memory and learning center of the brain is primarily the hippocampus, which is located in the temporal lobe of the brain and just above each ear. Within this structure, effective learning is often described by neuroscientists as a result of Hebbian plasticity. This concept, coined by Canadian psychologist Donald O. Hebb, illustrates that a neuron in close enough proximity to another neuron that repeatedly fires on it will strengthen the synaptic transmissions — the way that two neurons communicate through small electric impulses — between the two cells. Consequently, the dendrites — the branches on neurons that receive information — become larger in number and size in the neurons involved. The benefit of this strengthened connection is that the pathway will become more detectable than the average synaptic transmission. This way, retrieval of information becomes easier and quicker, meaning you will not forget the information as easily. Essentially, as Hebb famously states,“neurons that fire together, wire together.”

Memories can be created in either short-term or long-term form. In order to promote long-term memory, neurons must fire onto one another in a pattern called long-term potentiation, or LTP. This concept is one of the core ideas behind the larger idea of Hebbian plasticity. Basically, LTP postulates that upon frequent activation, the pre- and postsynaptic neurons will change the plasticity of a pathway to enhance its strength. LTP has specificity between different pathways, but can concurrently cause association of ideas if both neurons fire at the same time. This characteristic is especially useful when learning about several new concepts simultaneously, as it allows the brain to create a foundational “big picture” and connect pieces of information for easier application. These amazing mechanisms can only be used efficiently if one strictly practices repetition and application of their learning material. So, how can one accomplish this?

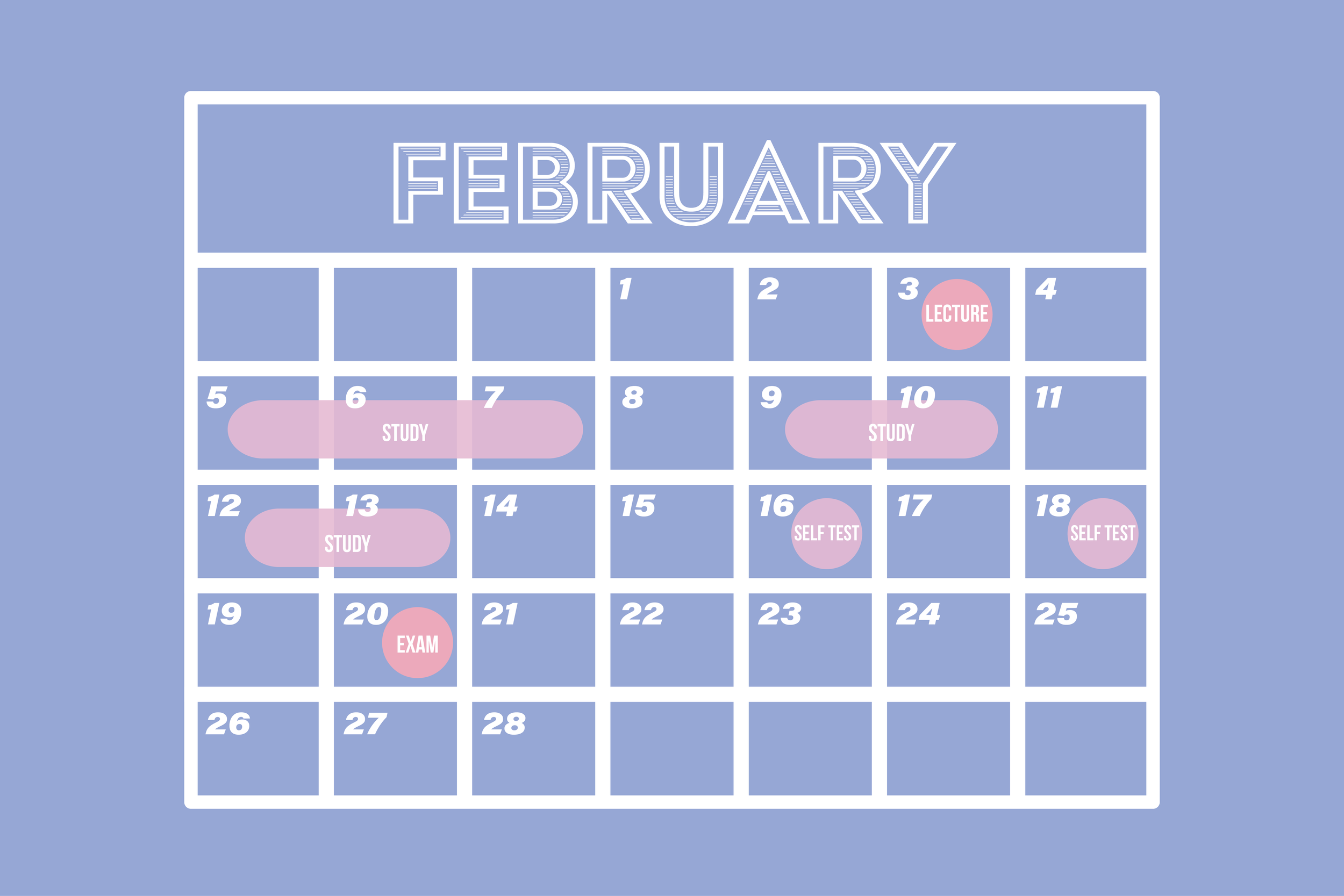

Backed by decades of research, scientists have found that the most effective study methods are spaced repetition and practice testing. These two methods are quite simple in nature, but what makes them hard to practice is their need for self-discipline. It is up to the student to apply these strategies consistently and with maximal effort to reap the benefits. Over the course of several days, students can expect to have a strong foundational understanding of their material that will not waver by test day: all in less study time than they could have imagined.

Dr. Linda O’Reilly, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh, shared her wisdom on this topic. She has taught at the University for the past six years, researched in various labs for two decades prior, and found a special interest in “the science of learning” around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Her focus on creating the perfect curriculum for her students is backed by spaced repetition and practice testing retrieval methods.

Specifically, spaced repetition is an initial study strategy that is ideal for making material stick in the brain. Oftentimes, students will look at the material once and then never again—until the night before the exam. As a result, they might complain about losing the information they memorized when they need it the next day. “These students confuse familiarity for actual knowledge,” Dr. O’Reilly explains. Spaced repetition is a foolproof method that solves this issue. To effectively use this strategy, students should review their material in systematic intervals, gradually increasing the time in between reviewing as they memorize. They might even find that cycling through different subjects is beneficial to create these breaks in learning. This way, hippocampal neurons are being fired often and at strategic intervals to ensure remembrance.

In addition, Dr. O’Reilly utilizes a “flipped classroom” lecture model to truly emphasize practice testing and active recall. Her students watch a set of “pre-lecture videos” and answer application questions on the topic before coming into class. She states, “For classes with a lot of information you have to process, the flipped classroom really helps to say ‘here’s the baseline I expect you to know,’ before we work on the concepts together.” Self-testing is a crucial step in the learning process because students can connect their knowledge to test their proficiency. Dr. O’Reilly explains, “The most important thing is the self-assessment. We have a bunch of practice questions before class along with the practice quiz question and lecture questions during class. Students have to really try and keep themselves accountable constantly.” This accountability is the main tenet of practice testing, as this periodic introspection can guide a student in the right direction. Learning is not linear, so studying should not be either. “As you’re going through and looking at your weaknesses, you should note them down and look at them as you’re going, and not at the very end,” Dr. O’Reilly adds. “You need to say to yourself, ‘I really need to focus more on this,’ even for the questions you got right, to build your confidence.”

Learning can be hard, but only if one makes it out to be. As a last word in the interview, Dr. O’Reilly shares, “Our hope is that when the lightbulb goes off for the students that they activate the pleasure center in their brains. We’re trying to create lifelong learners.” Using the power of neuroscience and self-discipline, anyone can make their learning experiences meaningful and enjoyable rather than grueling and confusing. If Sally were to use these techniques, she too might find ease in her studies like her roommate does!