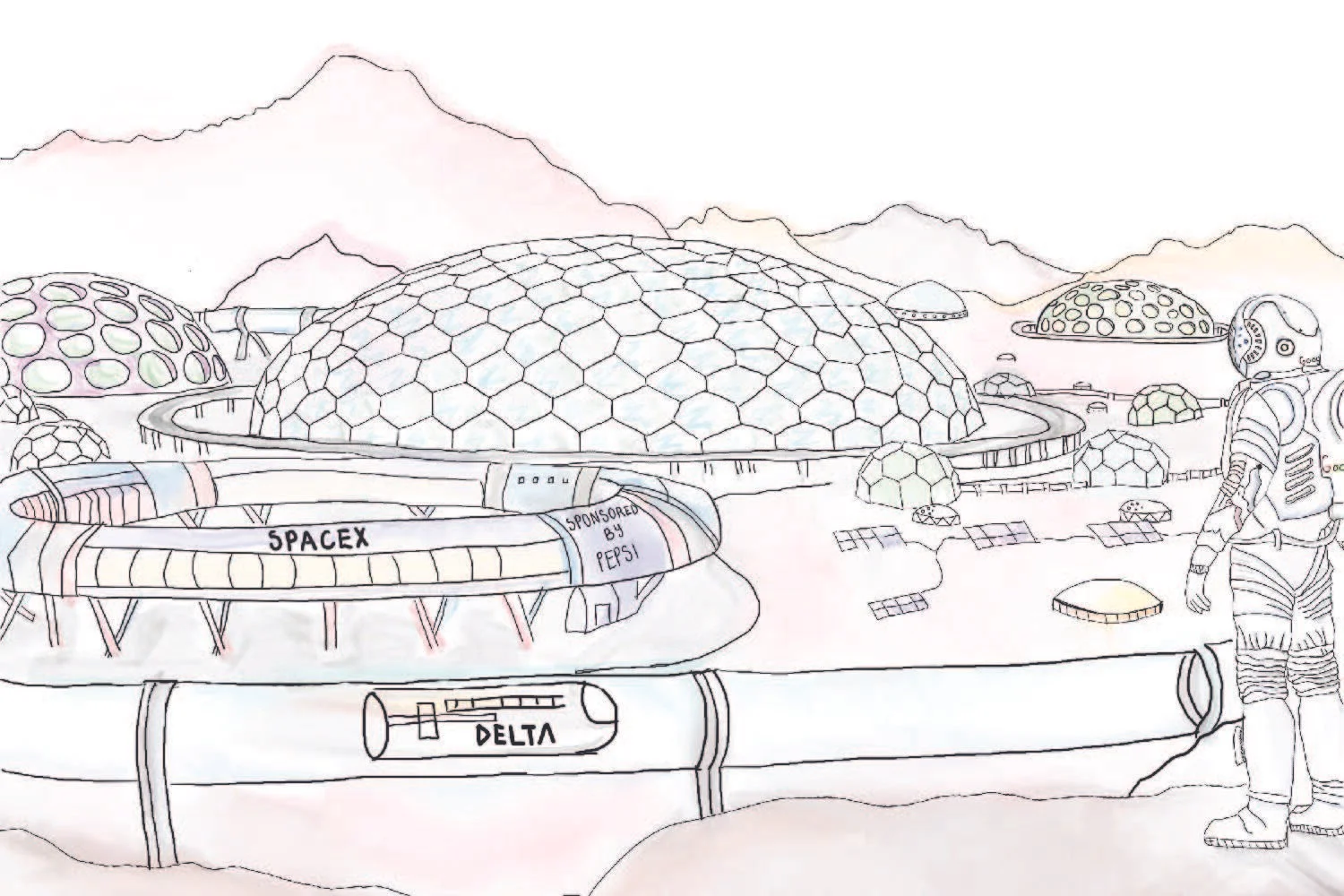

Banner by Julia Malnak

The Privatization of Space

By Reva Prabhune

Over a year and a half ago, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos successfully flew to the edge of space through his private spaceflight company, Blue Origin. This event was a historical one as it was an all-civilian suborbital flight. This flight contributes to the relevancy of the recent discussions around the privatization of space exploration. Historically, NASA has spent 85% to 90% of its budget on hiring private contractors to design and manufacture rockets and spacecrafts. But now, NASA often privatizes its whole operations as well. In May 2020, SpaceX successfully became the first private company to ferry two NASA astronauts to the International Space Station. The astronauts safely returned to Earth in August, and as early as November, NASA certified SpaceX to begin routine missions. This success also allowed NASA to collaborate with the private sector for their Artemis program. These commercial partners include SpaceX, owned by Elon Musk; Blue Origin, owned by Jeff Bezos; and the Alabama-based company Dynetics. Private firms such as these see the potential for a future in commercializing space beyond NASA contracts and satellite launches. For example, Bezos wants to build colonies beyond Earth; the company Virgin Galactic hopes to be the industry leader in space tourism; and other firms are pursuing asteroid mining for a new abundance of precious metals and rare earth elements. As you can see, all of these major companies’ goals are commercial rather than exploration- or research-based.

A serious problem with the privatization of space is that profit, rather than research, drives collaborating companies. As a result, private companies have little incentive to fund unprofitable space research, like many space exploration projects. Another problem is that accompanying space debris presents new environmental hazards. For example, SpaceX owns a satellite internet constellation called Starlink. According to Starlink’s official website, under the SpaceX division, they aim to provide the “world’s most advanced broadband internet system,” with an array of satellites that provide fast internet access anywhere on the planet. Musk aims to have almost 12,000 satellites circling Earth by 2027 and 30,000 more after that. To help you gauge the significance of this, consider that before SpaceX’s spree of satellite launches, there were only about 2,000 satellites in orbit. The logic is simple: the more items they put into space, the greater the odds they will start slamming into one another or other rockets and missions. There has already been one such collision in 2009 that produced significant orbital pollution in the form of 2,300 pieces of debris that scattered in all directions. Debris is a severe issue in space because even a marble-sized chunk, if traveling at thousands of miles per hour, is like a bullet that can render other satellites inoperable and unsteerable.

According to NASA’s article “Space Debris and Human Spacecraft,” more than 27,000 pieces of orbital debris are currently being tracked by the Department of Defense’s global Space Surveillance Network (SSN) sensors. But “much more debris — too small to be tracked, but large enough to threaten human spaceflight and robotic missions — exists in the near-Earth space environment.” If there is already this much debris that NASA cannot track, Musk’s mission of launching tens of thousands of satellites does not seem like a sensible idea. These risks make it clear that sending thousands of satellites up in a spree sounds reckless.

Commercialization also presents other problems besides space debris. In a 2012 interview at the American Museum of Natural History, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson said that he professionally believes that while private enterprises can handle routine space flight, they are unable to bear the large and unknown risks of advancing the space frontier. And part of what makes this privatization of space so chaotic is that Low Earth Orbit is currently very, very unregulated, akin to the Internet in the early ’90s.

Currently, the Outer Space Treaty is the primary space regulatory document, and it was signed in 1967 by all the major space-faring nations of the time. This treaty bans the use of weapons of mass destruction and posits that space and celestial bodies must be free to explore by all countries, so it is explicit in that nobody can travel to another planet or the Moon and claim that territory as their own. The problem with this treaty is that the private space sector was not around at the time, so there is nothing in it that posits what private companies can or cannot do. As long as they do not use nuclear weapons or claim celestial land for themselves, companies are essentially able to do what they want. Therefore, no regulatory agency within the United States government can “authorize and continually supervise” non-governmental space exploration. The report “Review and Assessment of Planetary Protection Policy Development Process” by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2018 called to remedy the private-sector gap by recommending that Congress pass legislation that “grants jurisdiction to an appropriate federal regulatory agency” in order to approve and oversee private-sector space activities that raise planetary-protection issues. This would be a logical small-scale solution. A more comprehensive solution would be to restrict private space companies. There is a larger conversation to be had about the ways and the extent to which private companies could be restricted. But one way the U.S. federal government can start to accomplish this goal would be to limit private funding of Mars colonization initiatives.

A much more impactful and even larger-scale solution would be to create something like Alaska’s sovereign wealth fund that delivers a percentage of its revenue to its residents. What would happen if we could establish a sovereign wealth fund for the entire Earth? Second Thought’s video “Who Benefits from the Privatization of Space?” explores this idea thoroughly. With this fund, countries involved in extraction would of course be compensated, but the wealth would be distributed democratically. What kind of future would be possible if we were able to establish such a world sovereign wealth fund? First of all, this program could create a global universal basic income. Countries could invest in clean energy, public works programs, education, and their own space programs. In addition, the plentitude of rare elements mined from space could expand automation and increase output, reducing the necessity of human labor and improving efficiency. As the video also explains, a space sovereign wealth fund would allow us to elevate all people and move towards a more egalitarian world. To avoid a disastrous dystopia with an increase in inequality, as a planet and human race, we must ensure an equitable distribution of the money we earn from space resources.

Privatization leads to environmental risks and other issues concerning commercial motives that hinder scientific research and exploration. As author Lewis Soloman warns in his book The Privatization of Space Exploration, “With for-profit enterprises carving out a new realm, it is entirely possible that space will one day be a sea of hotels and/or a repository of resources for big business. It is important that regulations are in place for this eventuality.” It is necessary that with whichever regulations we advocate for, both scientific and environmental concerns are taken into account, not just the needs of the private sector.